Equivalence and Gateways

“A picture is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know.”

| Diane Arbus

Every now and then I’m asked what makes a good photograph. What looks like a simple answer at first glance quickly turns out to be a more complex problem. Therefore, I decided to write this blog article to describe photographs as gateways in search of meaning.

From Pictorialism to Equivalents

In between 1885 and 1915 Pictorialism was a dominating trend and movement in photography. Pictorialism presented photography as an art form and initiated discussions about the artistic value of photography. Instead of using photography as visual, documentary records, Pictorialists prioritized the aesthetic value, composition, and tonality over accuracy. As such, Pictorialism initiated debates about the usage of the darkroom and the social role of photographic manipulation. A discussion that today is more popular than ever. In the early 1920s, Alfred Stieglitz created and communicated his concept of Equivalence. It seemed like a significant progression of his early, pictorialist work. For a period of about ten years, Stieglitz created a series of photographs featuring clouds in the sky. He called the series Equivalents. This series is recognized as one of the first intentionally abstract photographs. In this series, Stieglitz liberates clouds from the literal interpretation: “Through clouds to put down my philosophy of life – to show that my photographs were not due to subject matter […] clouds were there for everyone […] free”. With his technical skills (at that time, clouds were technically very difficult to photograph, as Stieglitz highlights in his article from 1923), but also with his spiritually rich photographs he inspired a whole group of younger photographers, such as Paul Strand, Anselm Adams or Eliot Porter. “Only some ‘Pictorial photographers’ when they came to the exhibition seemed totally blind to the cloud pictures. My photographs look like photographs – and in their eyes they therefore can’t be art. As if they had the slightest idea of art or photography – or any idea of life. My aim is increasingly to make photographs look so much like photographs that unless one has eyes and sees, they won’t be seen – and still, everyone will never forget them having once looked at them.” (all citations are from his 1923 article).

Equivalence and Gateways

In 1963 Minor White wrote an article about Stieglitz’s concept of Equivalence. White distinguishes three levels of Equivalence: First, he refers to Equivalence on a graphical level based on a photograph as a visual experience, not an object. “If the individual viewer realizes that for him what he sees in a picture corresponds to something within himself – that is, the photograph mirrors something in himself – then his experience is some degree of Equivalence” (p. 17). Second, White’s second level of Equivalence refers to the viewer looking at the photograph and his “correspondence to something that he knows about himself” (p. 17). Third, the third level of Equivalence draws a situation, in which the viewer doesn’t see the photograph anymore, but remembers the photograph. Because “we remember images that we want to remember”, it is about the inner sense of emotion and experience through that recall. White continues by arguing that when a photograph functions as Equivalent, then what the photographer “[…] had a feeling about was not for the subject he photographed, but for something else”. He concludes that therefore good photographs have an “expressive-evocative quality”.

Photographs are therefore gateways to something else. If we want it, or not. We often cannot deny the visual power of a photograph and what it does with us. Even bad images or images we do not want to recall, leave an impact on us, and sometimes it is hard to get rid of that impact. In the sense of Equivalence, photographs start conversations between the photographer, and the viewer and act as a medium for suggestibility and response.

To underline the idea of Equivalence, I’d like to quickly talk about three of my photographs – without going into much detail. This first photograph is from my series “Transitions“. In my artistic statement about this series, I wrote that “Transitions start in one place and end in another. For me, this photograph is symbolic of this pathway with stairs leading into an uncertain, nebulous upper state.

The second example is from my series “Harvesting the Pattern Puzzle” which documents the tough life of seaweed farmers. Two workers walk along the river, filled with little water at low tide, to set up the bamboo poles on which the soon-to-be harvested seaweed will be dried. The S-curved river looks like a separation between life and work, and workers move along a narrow but necessary thin line between the two sides.

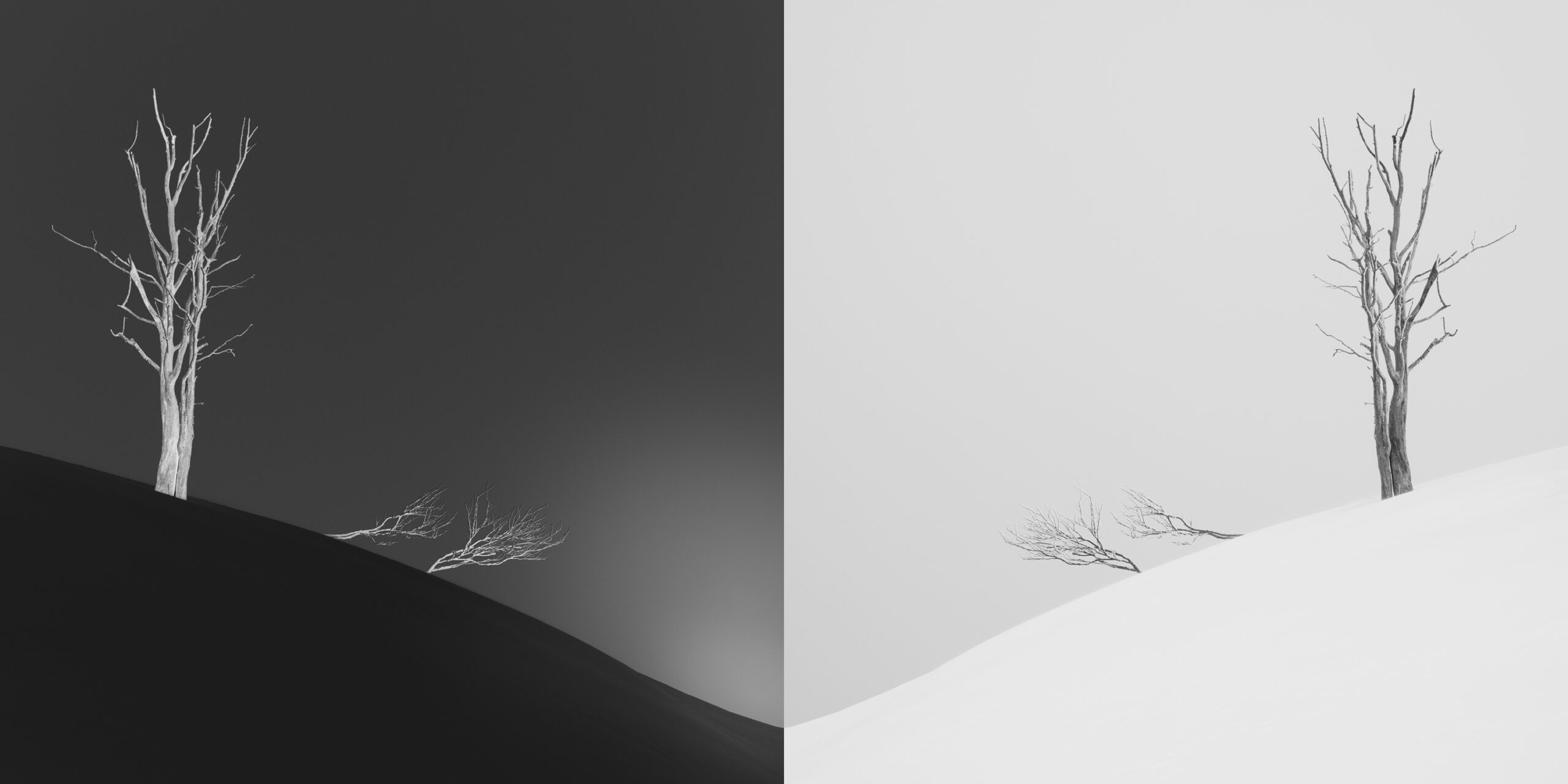

Finally, the third example is from my series “Together“. The series examines the differential relationships between the individual and the group. I used trees living at a location I consider my home as subjects. In this photograph, titled “Competition”, it looks like three trees are competing for sun, water, and soil. Each image in the series mirrors a different social concept, but all concepts may have a positive and a negative connotation. Competition may be a positive source of inspiration to proceed, continue and innovate, but it can also be destructive. These two sides reminded me of Yin & Yang, why I mirrored and inverted the image to create the final dyptich.

What Makes a Great Photograph?

Closing the loop and answering the initial question of this blog post: What makes a great photograph for me personally? Good photographs are – as Susan Burnstine said in a talk about her portfolio “Absence of Being” – a search for meaning. At best they start asking questions and continue to ask even more questions through ambiguity, metaphors, or symbols. Then, a photograph leaves the state of only being decorative art to become a reflection of the mental idea of the photographer.

How Can You Create Meaningful Photographs?

To answer this question, you have to ask yourself what meaning you are searching for? Having this metaphor and meaning in mind while you capture the photograph, it’ll be carved into the resulting visual experience arousing similar states in others. Through this process, the photograph becomes a self-portrait of the photographer and shows parts of her or him. Fascinatingly, our unconsciousness always finds pathways to get heard and our psychology listens by seeing things the unconsciousness wants to see. Therefore, I believe that looking back into your archive searching for repeating visual ideas may tell you a lot about who you are.

What do you find in your archives?

Reference:

Alfred Stieglitz (19 September 1923): “How I came to Photograph Clouds“. Amateur Photographer and Photography: 255.

Minor White (1963): Equivalence: The Perennial Trend, PSA Journal, Vol. 29, No. 7, pp. 17-21.

Richard Whelan (1995): Alfred Stieglitz: A Biography. NY: Little, Brown, especially chapter V “The real meaning of art”.