Meeting Michael Kenna

„The amazing things that happen when doing photography.“

| Michael Kenna

A dogma. Today, we face too many dogmata. Some are of political, some of religious, other of philosophical origin. But they all have in common that they claim to be the absolute truth. A mandatory binding statement. While the meaning of a dogma in the Ancient Greek was „something that seems to be true“, it has shifted towards an absolute truth. Is there something like an absolute truth? Doesn’t the acceptance of a dogma limits our perception and understanding of the world? If this is true, why should we then follow one?

Personally, I have never been a friend of following any dogma. I have also never idealized role-models. However, I do recognize many influences in my life: my parents, family, friends or mentors that all impacted the way I think, feel and act.

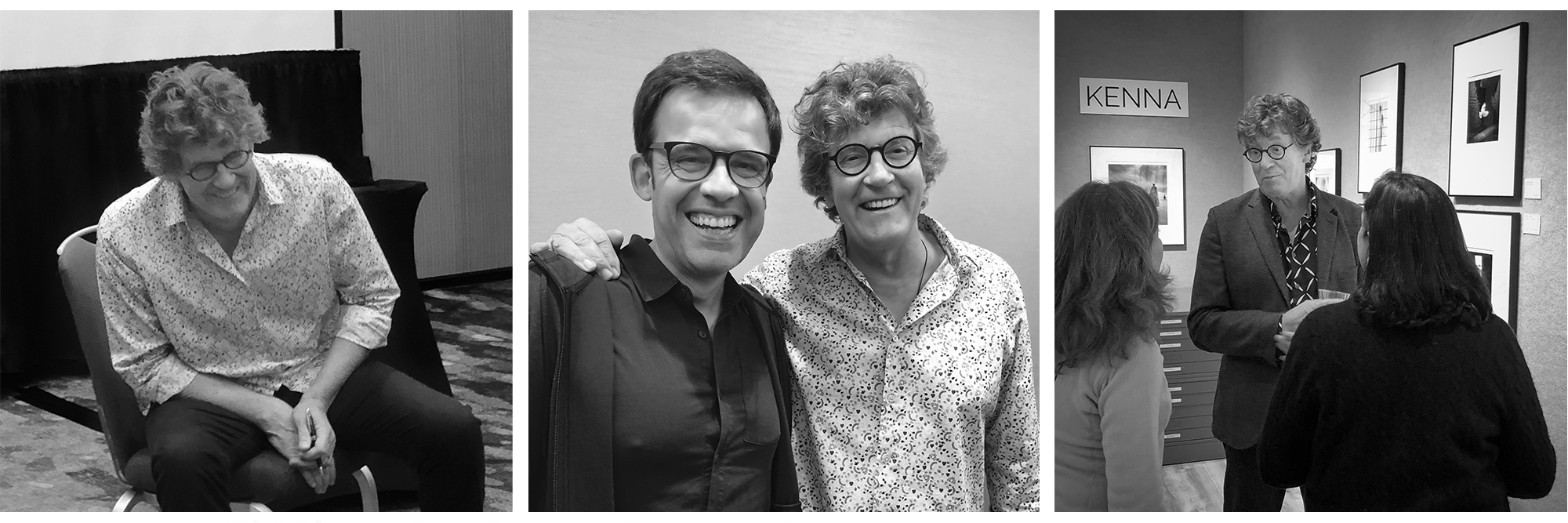

Today, in this blog article, I’d like to talk about an artist that also tries to not follow any dogma and who had a strong influence on my artistic and creative path: Michael KENNA. I recently had the opportunity to listen to a talk by him, to participate in a Q&A session with him and share some meals together. This article is based on these discussions we shared, enriched with some original quotes and my subjective personal opinions.

Michael KENNA is potentially one of the most well know landscape photographers in the world. He was born in 1953 in Widnes, Lancashire in the northwest of England. He studied at the Banbury School of Art and in the London College of Printing. While in the beginning he worked as advertising photographer in London, he moved to San Francisco in 1977 to become the assistant of Ruth Bernhard. As he himself says, these eight years of working aside of one of the visionaries in photography influenced him in many ways, especially in the creative handling of film negatives. He is still using his traditional film cameras along with the playful Holga camera.

My first impression of Michael watching him to prepare his talk was that he is very agile, the way he thinks, moves and acts. I had the impression that there is someone talking with the wisdom and experience and decades, but in a body and mind of a young man. His curiosity and deep interest in human and nature is obvious. Up until today, he has been interested in the impact of mankind on our natural environment, or as Michael says the „juxtaposition between landscapes and structure“ in which „the patina of the past is visible in the present“. Although most of his photographs leave humans out, one does feel their presence. This presence of the absence is an important idea in Michael’s work. He prefers to leave the description of his work to others and emphasizes suggestion over specific description. When the artist is present in his work, this may limit the audience’s imagination as they follow the lead of the artist. „Not knowing is amazing, it is inquisitive“ or framing it slightly different „doubt is central café“. As such, Michael’s work is more like an invitation to the viewer to participate.

While we went through many of his photographs in his talk, Michael always commented to them based on his immersion into the corresponding cultures the photographs has been made in. It was very obvious that he loves to get in touch with the people, the languages, the food, the architecture, the needs, but at the same time that he enjoys being out their on his own and to be surprised what the natural environments presents to him. „I grave silence. I like being along listening to myself.“ Which is never really completely true, because there is always the „other“ element in Michael’s work, the object itself that seems to accompany Michael during his process. Often, trees are the object in his art and Michael has a special connection to trees. He considers them as friends, visits them frequently and even asks them for permission to collaborate: „Hi tree, let’s do something together.“

In his work, Michael seems to always control the chaos and find another angle of simplification. „I am a collector in visible ways.“ While one can see Ruth Bernard’s influence and her idea of the „gift of the common place“, Michael’s work seems to offer escapes from reality. „Creating pathways where people want to go, but don’t end up and are not able to see the end“. As such, we don’t know where we are going. This idea is repetitive in his work and one can often discover it as a path into the light. On the other hand, one can clearly see Michael’s preference also for the darks as areas to imagine what could have happened in here.

To young photographers, Michael had some very insightful recommendations.

My Top 5 Take-Aways from Meeting Michael Kenna

1. Focus more on the journey. „Once you see the journey, you don’t need the destination.“

2. „Get your eyes under control“. But „face yourself to loose control“. Create the ability to doubt yourself, be never confident nor satisfied but critical and hungry.

3. „Leave things not quite perfect and give others a chance to figure it out. The more we clean things up, the less interesting it becomes.“

4. „Once you found balance, search for imbalance. It is the imperfection that makes the photo“.

5. Allow for the „fortuitous happenstance“ or the accidental emergence of natural humanity and humanity in nature to come through. Or to frame it differently with Michael’s own words: „I am heavily inspired by Jetlag.“

Meeting Michael has been a very impactful moment for me and I wish we all will be capable to preserve this agility in everything we do and create.

In agility.

References

Kenna, Michael, homepage, http://www.michaelkenna.net/, 28012020.

Baskerville, Tim, On the Shoulders of Giants. An Interview with Michael KENNA, in: The Nocturnes, July 1995, http://www.thenocturnes.com/resources/kenna.html, 28012020.